When Mussolini came to power, Rome became his laboratory of myth-making. Through architecture and urban design, fascism sought to transform the city into a visible theology of power – a modern empire built upon the ruins of the ancient one. The Foro Mussolini (today Foro Italico) stood at the heart of this vision: a vast ensemble of marble stadiums, mosaics, and processional avenues where sport, art, and ideology merged into a single ritual of obedience. This article explores the ideological construction of fascist Rome through the lens of the Foro Mussolini, conceived as a monumental synthesis of classical heritage and modern rationalism. The complex embodied the fascist ideal of Romanità, the revival of the ancient Roman spirit as a source of political legitimacy and moral regeneration. Further it examines the Foro’s afterlife, its transformation, neglect, and reappropriation, as a case of dissonant heritage. The enduring presence of its fascist symbols reveals Italy’s ongoing struggle to negotiate its monumental past between erasure and reinterpretation.

Introduction: Rome as a laboratory of power

When Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922, one of his earliest and most enduring obsessions was the symbolic reconstruction of Rome. In his speeches, Mussolini repeatedly described the city as the „heart of civilization“ and as the spatial embodiment of Italian destiny1. To him, Rome was not merely the capital of the Kingdom of Italy but the epicentre of a new imperial project, therefore a modern continuation of the Roman Empire under Fascist leadership. The Duce’s ambition was to transform the urban fabric of the city into a visible and permanent monument to the regime, where architecture, urban planning, and public ritual would merge into a single language of power. This vision was grounded in the ideological concept of Romanità, the idea that the ancient Roman spirit could be revived to provide moral, aesthetic, and political legitimacy to modern Italy. As Aristotle Kallis notes, Fascism appropriated the legacy of the Caesars to root its revolutionary project in the familiar and reassuring grandeur of the past producing a potent myth of continuity between antiquity and modernity2. Through this myth, Mussolini claimed that Fascism would complete the historical cycle of Italian civilization: the Rome of the Caesars, the Rome of the Popes, and now the “Third Rome”: the Rome of the Fascists3.

To translate this vision into stone, the regime launched an ambitious program of architectural and urban interventions that redefined the city’s skyline. Major works included the construction of the Foro Mussolini (today Foro Italico4), a vast complex of stadiums, mosaics, and marble avenues designed to embody Fascist ideals. At the same time, older neighbourhoods were demolished to open new vistas toward ancient monuments, such as the creation of Via dell’Impero (now Via dei Fori Imperiali), a grand avenue linking Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum5. These interventions were meant not only to glorify the past but also to inscribe Fascist ideology into the very geography of the city, fusing historical continuity with modern totalitarian control.

Architecture became a key tool in what historian Emilio Gentile has called the „sacralization of politics“6. By endowing political authority with religious and aesthetic dimensions, Fascism sought to create a civic religion centred on the cult of Rome and the cult of the Duce. Public spaces were conceived as modern temples: the Foro Mussolini functioned as both a sports complex and a sacred arena of youth formation. Every building, statue, and inscription was designed to evoke both obedience and awe, transforming the citizen into a participant in the regime’s liturgy7.

In this sense, the urban fabric of Fascist Rome can be read as a vast ideological text. The rationalist forms favoured by architects such as Marcello Piacentini, Enrico Del Debbio, and Giuseppe Pagano reflected a conscious attempt to merge modern functionality with the grandeur of antiquity8. The materials (marble, travertine, concrete) were chosen for their permanence and symbolic purity. Symmetry and axiality, recurring features in Fascist urban design, conveyed the order and discipline that the regime claimed to embed in society9. These buildings were not merely expressions of architectural taste but instruments of political pedagogy embodying a moral vision of hierarchy and collective strength10. The political function of architecture extended beyond the city’s physical transformation. Monumental construction projects served to mobilize labour, demonstrate the efficiency of the regime, and visually affirm Mussolini’s personal authority. Giant mosaics, inscriptions such as DVX, and statues of idealized athletes turned public space into an arena of ideological performance11. These symbols were omnipresent and inescapable, shaping both the physical environment and the consciousness of those who inhabited it. Fascist modernism relied on a “palingenetic myth”, a narrative of national rebirth through aesthetic order and collective unity12. Rome, therefore, became the most powerful stage for this political theatre: a city simultaneously sacred, profane, eternal and revolutionary.

By the time of the regime’s collapse in 1943, much of Mussolini’s “Third Rome” remained unfinished, yet its architectural imprint was indelible. The city’s Fascist monuments continue to provoke debate in contemporary Italy: are they artistic achievements to be preserved, or ideological relics that should be contextualized or condemned? Postwar administrations alternated between removal, neglect, and reinterpretation of Fascist sites, reflecting the nation’s uneasy relationship with its totalitarian past. In the case of Rome, these structures are not isolated ruins but living parts of the urban landscape, used, adapted, and reimagined by successive generations.

The myth of Romanità and the construction of Fascist imagination

Among the most enduring ideological inventions of Mussolini’s regime was the myth of Romanità: the cultural, moral, and political idea that Fascist Italy was the rightful heir to the Roman Empire13. The word itself, derived from romanus, had existed in Italian intellectual discourse since the nineteenth century, but under fascism it acquired a new, totalizing meaning. As Emilio Gentile explains, Romanità was transformed into a “civil religion” a sacred narrative that fused ancient history with the modern revolutionary mission of fascism14. It provided the regime with a symbolic language through which it could legitimize its authority, connect the dictatorship to a glorious past, and project that past into a vision of imperial modernity.

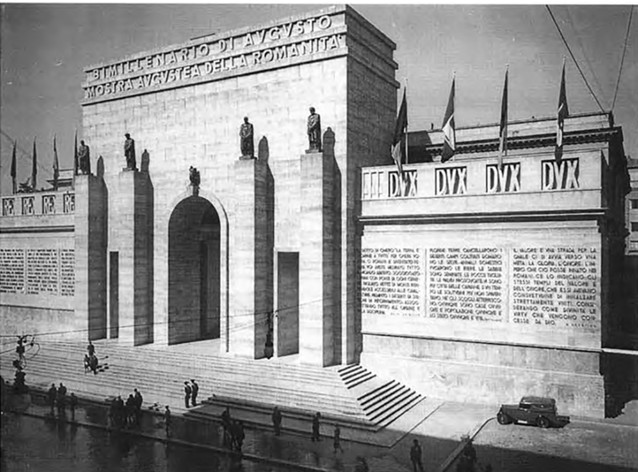

The cult of Romanità permeated all aspects of Fascist culture. Mussolini proclaimed that „Rome is our point of departure and our point of reference“ presenting himself as the new Augustus who would complete the historical cycle of the Italian nation15. Institutions such as the Istituto di Studi Romani16, founded in 1925, were charged with promoting research and propaganda around ancient Rome, while journals like Capitolium and exhibitions such as the Mostra Augustea della Romanità (1937) (Fig.1) visually articulated the continuity between the Caesars and the Fascist regime17.

In this ideological framework, archaeology, architecture, and education became instruments of state-building. Romanità was a unifying cultural code that bound intellectuals, artists, and bureaucrats in a common vocabulary of national regeneration. This reappropriation of antiquity was not an antiquarian exercise but a modern political project. Fascism’s relationship to the classical past was pragmatic and performative: it sought to reinterpret Roman grandeur through the lens of twentieth-century technology and aesthetics18.The monumental architecture of the 1930s exemplified what historian Richard Etlin calls the „aesthetic of authority where the visual language of power combined ancient forms with modern abstraction“19. In Mussolini’s Rome, the classical column stood beside the steel truss; marble surfaces coexisted with reinforced concrete. The goal was not to replicate the past, but to absorb its aura into a modern regime of order, hierarchy, and discipline.

Fascist architects, most notably Marcello Piacentini, Giuseppe Pagano, and Enrico Del Debbio, were instrumental in constructing this aesthetic synthesis. Piacentini’s concept of classicità moderna (modern classicism) defined the official architectural style of the regime: rational, monumental, stripped of ornament but imbued with symbolic gravitas. Architectural historian Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi argues that Fascist design translated ideology into form, producing a “theatre of power” in which space and monumentality functioned as visual metaphors for authority and obedience20. The resulting urban environment, from the symmetrical axes of the E42 master plan to the athletic arenas of the Foro Mussolini, performed Romanità as a lived, spatial experience.

The Fascist manipulation of history extended beyond architecture. Rituals, festivals, and education all served to embed Romanità within everyday life. The Natale di Roma (the traditional “Birthday of Rome” celebrated on 21 April) was elevated to a national holiday, staged with parades and torchlit ceremonies in the ancient fora. The introduction of the Era Fascista calendar in 1926 symbolically reanchored historical time to Mussolini’s rise to power, as if Fascism itself were the new foundation of civilization21. Youth organizations like the Opera Nazionale Balilla and the Gioventù Italiana del Littorio trained boys and girls to see themselves as heirs to Roman legionaries, blending militarism, physical education, and mythic history into one cohesive pedagogy22.

Colonial expansion further intensified the rhetoric of Romanità. The invasion of Ethiopia in 1935–36 was framed as the return of Rome to Africa. In propaganda films and speeches, the conquest was presented as the fulfilment of destiny — the idea that Roman civilization was returning to its natural empire. Posters depicted modern Italian soldiers as new centurions, and African landscapes were rendered as stages of imperial redemption.

But Romanità also had a psychological and moral dimension. The regime constantly invoked Roman virtues (virtus, disciplina, fides, gravitas) as ethical models for the modern citizen. Schools and propaganda films alike stressed the duty of sacrifice for the collective, the subordination of the individual to the state, and the continuity of Italian greatness across millennia. This moral rhetoric intersected with Fascist gender ideology: the virile Roman warrior and the maternal matron became archetypes for Fascist masculinity and femininity23. Through such symbolism, the body itself became a vessel of Romanità: disciplined, pure, and productive. Yet the myth was fraught with contradictions. As historian Roger Griffin argues, Fascism’s “palingenetic myth” (the promise of national rebirth) depended on a paradoxical fusion of futurism and archaism. The regime’s appeal to ancient Rome was not a retreat into nostalgia but an attempt to reimagine modernity through mythic time. This tension produced a distinctive aesthetic: the simultaneity of past and future, empire and revolution24.

By the end of the 1930s, Romanità had become institutionalized in both material and symbolic form. The Mostra Augustea della Romanità of 1937, marking the 2000th anniversary of Augustus’s birth, epitomized the regime’s historical appropriation. With over 3,000 artifacts and models of imperial architecture, the exhibition equated Augustus’s Pax Romana with Mussolini’s Fascist order25. The event was both a scholarly endeavour and a grand propaganda spectacle, staged in monumental halls and accompanied by films, catalogues, and school visits.

Romanità served as Fascism’s most successful myth because it offered both continuity and transcendence. It provided Italians with a sense of belonging to a grand historical cycle, while masking the regime’s violence under the veneer of civilization and beauty. It turned the ruins of antiquity into instruments of political pedagogy, binding aesthetics to authority and the city to the state. In doing so, Mussolini’s Rome became more than a capital, it became a stage where the myth of eternal Rome was resurrected in marble and myth alike.

The Foro Mussolini / Foro Italico: birth of a Fascist sanctuary of sport

The Foro Mussolini, inaugurated in 1932 and later renamed the Foro Italico, was one of the most coherent material realizations of Fascist ideology in urban form (Fig.2).

It encapsulated the regime’s ambition to create a new social order through the discipline of the body and the aesthetics of collective strength. The project originated in 1927 as the Foro della Gioventù, promoted by Renato Ricci, head of the Opera Nazionale Balilla, and executed by the architect Enrico Del Debbio, later joined by Luigi Moretti. Situated at the foot of Monte Mario, the Foro was conceived as a vast campus for physical education and state ritual. Its composition combined modern spatial rationality with classical symbolism: processional avenues, axial symmetry, travertine colonnades, and marble statues of idealized athletes. The Stadio dei Marmi, ringed by sixty statues representing Italian provinces, embodied what can be described as a national hymn to youth and harmony.

The regime’s focus on physical culture reflected Fascism’s anthropological ambition to forge the uomo nuovo (new man)26. Physical training was not an end in itself but a political act, an instrument for moral regeneration and civic obedience. The Foro Mussolini thus functioned as a “sacred gymnasium” where the citizen’s body became an expression of state power.

The design language of Del Debbio and Moretti exemplified the regime’s dual allegiance to classical tradition and technological modernity. The complex’s monumental staircases, obelisks, and inscriptions evoked imperial Rome, while its strict geometry and reinforced concrete reflected modernist efficiency. The materials (like white marble and travertine) were carefully chosen for their association with Roman heritage, yet their arrangement followed the rationalist vocabulary of 1930s architecture27. The Foro’s urban choreography was also pedagogical. Visitors entered along the Viale del Foro Mussolini (Fig.3), lined with cypresses and mosaics celebrating Fascist slogans and military victories28. The progression from entrance to stadium was designed as a moral ascent: from the mundane to the exalted. In this, the Foro echoed the spatial logic of ancient Roman fora, where political authority and public virtue were inscribed in stone29.

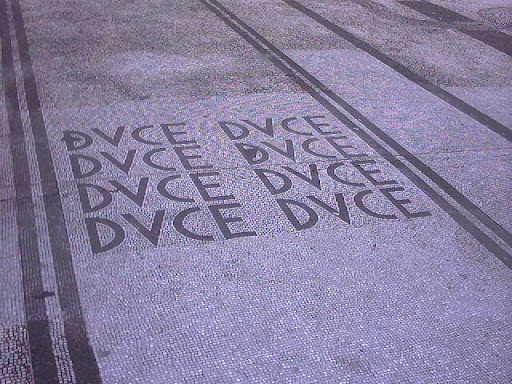

Events staged here were spectacular and highly codified. The Saggi ginnici, mass gymnastics demonstrations by Fascist youth, transformed the site into a vast living tableau of loyalty. Mussolini often presided in person, greeting thousands of athletes performing synchronized routines beneath the obelisk30inscribed MUSSOLINI DUX31.

The Foro Mussolini thus stood at the crossroads of art, propaganda, and pedagogy. Its mixture of classical iconography and modernist abstraction epitomized the Fascist quest for unity between past and future. „The Foro Mussolini did for Fascism what the Acropolis did for Athens, it translated political order into visible harmony “32.

The political symbolism of the Foro Italico

While ostensibly devoted to sport, the Foro Mussolini was fundamentally a political stage, a theatre of ideology. Its spatial order and iconography transformed athletic practice into a ritual of state worship.

At the complex’s focal point stands the Obelisk of Mussolini – as previously mentioned – erected in 1932 from a single block of Carrara marble, inscribed vertically with the colossal phrase MUSSOLINI DUX. Conceived by architect Costantino Costantini, it directly referenced both ancient Roman and Egyptian models while asserting the modern Duce as their heir. The obelisk served as a visual hinge between Rome’s imperial past and its Fascist present, uniting antiquity and dictatorship in a single form.

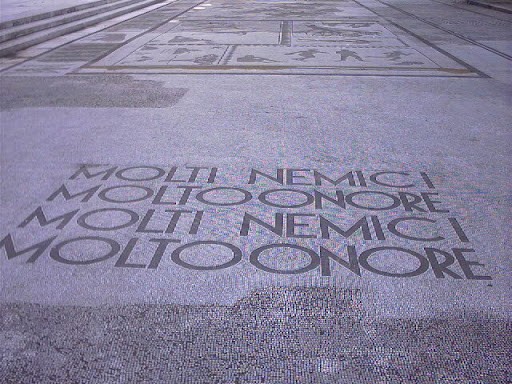

Around it, a mosaic pavement over 1,400 square meters in size depicts scenes of Roman legions, military eagles, and slogans of Fascist conquest. Its black and white tesserae – crafted by students of the Accademia di Belle Arti – recall the aesthetic of ancient flooring yet carry messages such as DUCE and MOLTI NEMICI, MOLTO ONORE (Fig.4 and 5). These inscriptions inscribed obedience into the landscape itself.

Ceremonial use reinforced these meanings. The Saggi ginnici turned the Foro into a monumental altar of loyalty. Thousands of participants formed geometric patterns representing the Fascist symbol, filmed and broadcast across Italy. The Foro’s ritual choreography made Mussolini’s presence ubiquitous, even when he was not physically there.

The Foro Italico also exemplifies the Fascist conflation of sport and militarism. Training grounds were imagined as “peaceful battlefields” where bodies were disciplined for future conquest. The Foro thus prefigured the militarized aesthetics of the E42 (EUR), shifting from the athletic to the imperial. Despite its overt symbolism, the Foro Mussolini was admired internationally. Foreign journalists visiting in the 1930s often praised its “clarity and order” perceiving in it a model for modern civic architecture.

From Foro Mussolini to Foro Italico: continuity and erasure

When the Fascist regime collapsed in July 1943, the monuments of Rome faced a new and uneasy fate. The Foro Mussolini was too large and too costly to destroy. Instead, the authorities opted for symbolic erasure: by decree of the Badoglio government, the complex was renamed the Foro Italico later that same year.

This act of renaming was more rhetorical than transformative. As Italo Insolera notes, „no statue was removed, no mosaic altered “The obelisk still proclaimed MUSSOLINI DUX, and the black-and-white pavements still glorified Fascist conquests. The city, exhausted by war, preferred to forget rather than confront33. Historian Brian Ladd calls this a „strategy of benign neglect“ through which postwar Rome absorbed Fascist architecture by stripping it of explicit ideology34.

In the 1950s, Rome’s urban authorities reclaimed the Foro Italico for national sports, emphasizing its utility rather than its symbolism. The 1960 Olympic Games marked a turning point: the stadiums and pools that once hosted Fascist youth parades became backdrops for the rebirth of democratic Italy. Yet television images of the games, broadcast globally, still captured the enduring marble inscriptions of the Duce, a reminder of architecture’s resistance to historical revision.

Postwar architectural critics reinterpreted the Foro Italico through a lens of aesthetic modernism. Figures like Bruno Zevi and Giulio Carlo Argan praised Del Debbio’s rationalism while condemning the politics behind it. This process of aesthetic reclassification allowed Fascist architecture to survive as “heritage” rather than „memory”.

Today, the Foro Italico illustrates Italy’s complex relationship with its authoritarian past. It is certainly an example of “dissonant heritage”, a term denoting sites where beauty and ideology coexist uneasily. The Foro continues to host major events, from international tennis tournaments to political rallies, its Fascist iconography simultaneously visible and ignored.

The Foro Italico is, indeed, not Fascism preserved, but Fascism sedimented, its ideology fossilized in form. Its endurance testifies to the difficulty of erasing power once it has been built into stone. Like Rome itself, the Foro Italico remains layered: the ancient, the Fascist, and the modern all coexisting in uneasy dialogue. The city’s challenge, even today, lies not in forgetting these layers but in learning how to read them.

Conclusion: between legacy and reinterpretation

The Foro Italico today represents one of the most challenging examples of difficult heritage in Italy. Its survival forces contemporary society to confront the question of how to relate to monuments built to celebrate a dictatorship. Rather than functioning as propaganda, it now serves as a space where history, memory, and civic responsibility intersect. The debate over the obelisk inscribed MUSSOLINI DUX illustrates the tension: some argue for preservation as a historical record, while others call for contextualisation or reinterpretation to prevent ideological normalisation.

Adding interpretive tools such as plaques, guided tours, or educational materials can make the Fascist origins of the complex legible without destroying its architectural significance. The site thus becomes a palimpsest: a place where layers of memory, political symbolism, and contemporary use coexist. The Foro Italico demonstrates that architecture can act as both a record of ideology and a tool for civic engagement. The challenge is not to erase history, but to interpret it responsibly, ensuring that the lessons of fascism remain visible, legible, and subject to critical reflection.

Biografie

DILETTA HABERL is art historian and PhD candidate at the University of L’Aquila. Her research focuses on the role of foreign travellers, particularly from Germany and the Netherlands, along the so-called Via degli Abruzzi between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Her interdisciplinary approach combines art history, travel literature, and cultural history. She graduated from La Sapienza Università di Roma with a master thesis on the Italo-German artist Herta Ottolenghi Wedekind zur Horst. This line of research has since evolved through publications and presentations at international conferences, contributing to the reassessment of women’s roles in the decorative and textile arts. Diletta Haberl is an active member of ICOM Italy and of its Lazio Regional Committee, contributing to the promotion of museum professionalism and the protection of cultural heritage. Her work is distinguished by a strong commitment to intercultural dialogue and to the enhancement of museums as spaces of inclusion, continuity, and innovation.