The visual essay focuses on how layered fabrics carry traces of knowledge and gesture, and how memory is inscribed through the hand. Perez draws on Lévi-Strauss’s notion of the bricoleur (The Savage Mind, 1962) as a figure who works with what is at hand, recombining fragments to generate meaning.

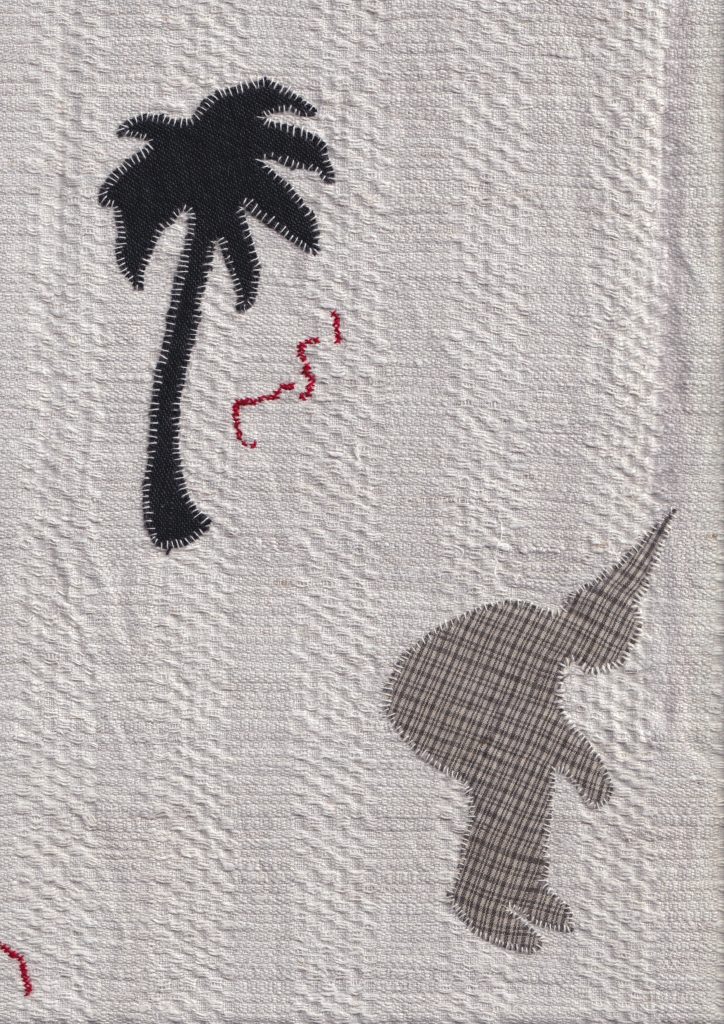

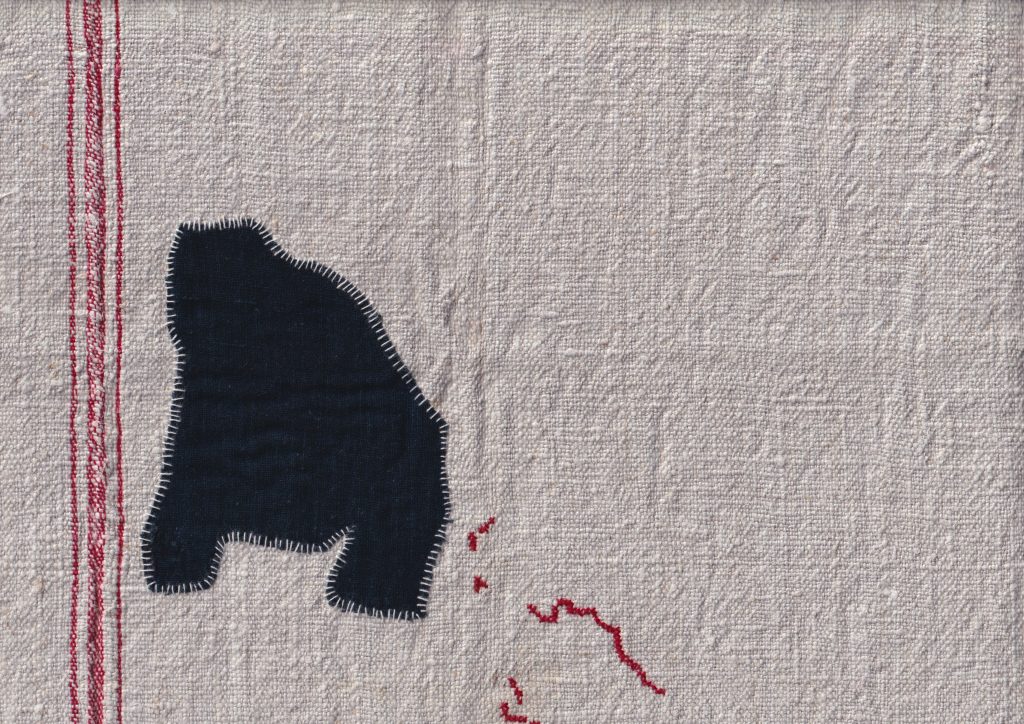

By combining high-resolution scans of fabric work with captured gestures of stitching, folding, layering, Perez explores how textiles can be both material surface and conceptual tool.

Sewing and repairing operate as acts of preservation and as forms of thought, where subtle and improvised gestures accumulate into an archive of lived knowledge.

Decentered Gestures reframes repair as an act of archiving where material fragments carry layered histories. Through bricolage, the maker weaves together past and present, generating new meanings from the dense traces embedded in fabric.

In The Savage Mind (La Pensée Sauvage, Paris, 1962), French anthropologist and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss discusses the practice of bricolage (crafting) as a form of a primary science. Originally, the French term bricolage described incidental activities such as games of chance (e.g. billiards or ball games), hunting, or horsemanship, always signifying a sideways or indirect movement. Today, the term bricolage or bricoleur refers to someone who creates crafts with their hands.

In Lévi-Strauss’s conception, the bricoleur is someone who works with whatever is at hand, assembling disparate fragments into new configurations, in contrast to the engineer’s linear planning. In fact, the practice of bricolage lacks any teleological aspect. The bricoleur is not defined by a guiding project but solely by their instrumentality, by the instruments and materials they have available.

The instruments or elements the bricoleur uses have multiple potential possibilities of becoming, though these possibilities are limited. All of these elements, considered as a kind of treasure, hold a range of possible meanings they can assume but are constrained by their own history and by what remains predetermined within them; such as their original function or the roles they have played in other situations. In a way, the bricoleur collects pre-transmitted messages that carry the density of human history. In that sense, every trace on the fabric (stitch, repair, crease, or wear) doesn’t carry only itself, but also a thick layer of humanity.

Every trace is a record of past gestures and a decentralized archive of experience. These marks form a constellation of fragmentary memories, with no clear hierarchy between old and new, main thread and detail. The textile thus becomes a palimpsest: each intervention displaces any singular center, generating multiple, shifting meanings. Each element is originally free of fixed form and function and can therefore open to transformation and new significations. Each element or object adopts a particular role, and by doing so, the entire structure of what is being crafted acquires a new meaning. The bricoleur works with a collection of cultural residues and gives them new form.

After doing the inventory of all theoretical and practical means that will delimit the possibilities of becoming of each element, the bricoleur reorganizes them and therefore they acquire a new signification. The poetry of bricolage finds itself in how the bricoleur tells, by making choices, his own life and character. “Without never fully achieving his project, the bricoleur always leaves a part of himself into it”.1

The scanned mended fabric therefore carries layers of past and new human history. The final result, filled with new signification, doesn’t address only itself but addresses somebody and something that was there before. Like the Saussurian concept of sign, the final image doesn’t address/refer only to itself but can also replace or signify something other than what it is. The final project of the bricoleur can only exist as a double signification: its actual limited possible form and all its past signification, both of them acting like old and new layers of a dense cultural humanity.

Biografie

JOACHIM PEREZ is a Swiss artist based between Germany and Japan. Trained in product design, Perez turned to textile installation to resist speed-driven production and embrace slower processes. Working with reclaimed fabrics and handcraft techniques, his work explores memory, repair, materiality and the social inscriptions of masculinity. Perez is currently working on several projects, including a large installation for Chemnitz 2025 Kulturhauptstadt Europas and one in Weimar.