Reflections on the entanglement of freedom and bondage, the inside and outside, past and present

Wie lässt sich der Wert eines (Kunst)Objektes bestimmen und wer besitzt die Macht dazu? Imke Felicitas Gerhardts Essay beschreibt eine fiktive Reise zweier real existierender Objekte, in welche sich die (Kolonial)Geschichte spurenhaft eingeschrieben hat. Eine Objektbiographie also, die die Verwobenheit von Geschicht(en) (entangled histories) zu illustrieren versucht. Der experimentelle Schreibstil und der Einbezug von transdisziplinären Ansätzen kann dabei als Kritik an institutionalisierten Formen westlicher Wissensproduktion verstanden werden. Der Essay versucht zu verdeutlichen, dass sowohl eine transkulturelle als auch eine transnationale Perspektive unerlässlich ist.

For the reader:

The following essay is a transdisciplinary attempt to illustrate the entanglement of histories by following two objects on their journey. Telling their stories, like writing their ‘object biographies’ should open alternative perspectives on the materiality of ones everyday world. The more experimental writing style and the use of theories from different disciplines is an attempt to critique and overcome institutionalised forms of western knowledge production. The essay tries to illustrate that a transcultural, as well as a transnational perspective is indispensable.

2010

London

A day in September

Concrete. Le Corbusier’s most desired material, or Modernity’s most desired material, or its expression. Metonymy.

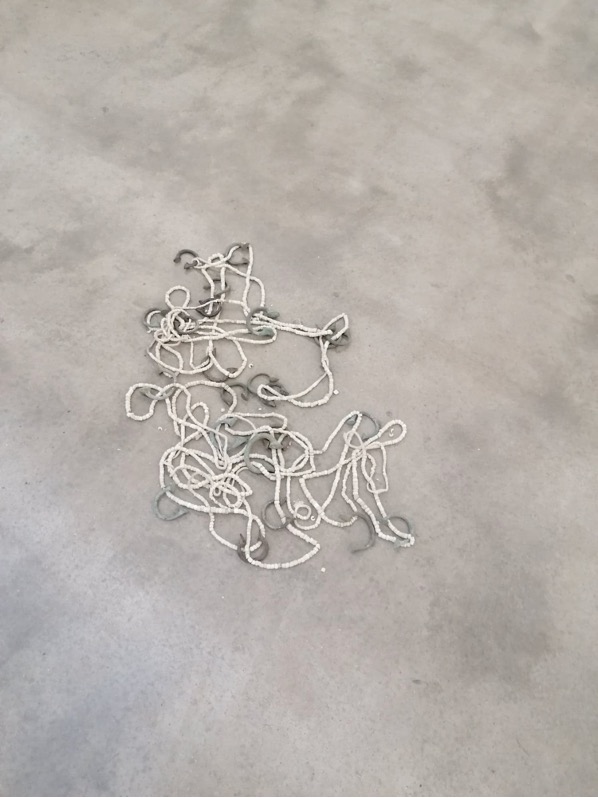

Concrete: an object. Here, in its clarity, in front of us: An Exterior Light, £26,250.1 (fig.1)

Le Corbusier, Exterior Light, from Chandigarh, India, 1952-1956, concrete, steel, glass, 88 x 87,5 x 57cm.

Image Credits: Phillips Auktionshaus – https://www.phillips.com/detail/le-corbusier/UK050210/1?fromSearch=corbusier&searchPage=2

Like nervous flies, pulled towards light. Here, by desire too. Fraught faces of bidders buzzing in speculation. An object, itsprice. Its value — in the future.

1796, Westminster London, the foundation of Phillips. An auction house, proud of its history, even prouder ofthe present — its presence, globally. Continuities.

“Le Corbusier, Exterior light, from Chandigarh, India, 1952-56, estimate £18,000-22,000.”2 Le Corbusier’slight for India, a vision, exterior, an Exterior Light, expired.

Wrested of its being. No longer an integrated part of a whole, of a building, extracted, singularized, like commoditized, pulled by its value, which is defined by its outside. The art market.

Its lines of flight, its change in nature (Deleuze), in migration. Being now the abstract of the abstract is the result of a process — of its commodification. A value, not innate, but infused, not only by exchange, but by culture, too. Igor Kopytoff calls it the moral economy. A cultural and cognitive marking of the thing, concealed by objective transaction.3 What is value?

Chandigarh, the planned city. India’s expression of a new beginning. A monument of modernity, built shortly after independence (1947). A masterpiece of Le Corbusier – the authority of modernity. A vision for a future — in decay. In 2011, The Guardian headline reads: “Le Corbusier’s Indian masterpiece Chandigarh is stripped forparts. Group rallies to rescue city built as monument to modernity from neglect and plunder.” “To plunder,” to steal, or to loot. A word, used in the context of war, or of colonialism. Continuities. The article goes on: “Recently, international art dealers have made substantial sums selling hundreds of chairs, tables, carvings, and prints designed by Le Corbusier and his assistants but obtained at knockdown prices from officials often unaware of their value.”4 Sold, too, is an Exterior Light, made of concrete, steel and glass, 88 x 87,2 x 57 cm. Auctioned for £26,250 in London. On a day in September. One dimensional currency.

Art, often imagined in this autonomous sphere, opposed, or exterior to the economic realm – to property relations – to power relations. And its spectator, the libertarian subject, contemplating on the latter, on its innate, insightful qualities, which stimulate this process of finding cognition through exchange. This process which should enable a higher truth.

This 18th century conceptualisation of Art in its difference — indeed, already questioned by the presence of a powerful art market and critiqued for being a bourgeois and western ideology in its nebulous elevation of the work of art and its premise on the enlightened spectator — nevertheless still shapes the conception of the artwork today. Perhaps because its perception is rooted and so deeply intertwined with our concept of the self, the autonomous subject and the object as its antithesis. However, conceptualised in the historical context of slavery and colonialism, this opposition, which pertains to be natural, is based on a racist opposition, and is, an inherently racial construction. It functions as the ideological groundwork for the distribution of value.

The synchronous emergence of a transatlantic capitalism, of slavery and colonialism, or, in other words, the co-constitution of the rise of a modern western civilisation and the exploitation and degeneration of everything which is discriminately constructed to be its outside — this entanglement, makes the purification of the economic and the cultural sphere indefensible. I’m speaking of the inseparatability of economic exploitation and cultural negation, of economic prosperity and cultural hegemony, manifested in its inextricability in the object itself (‘the object’ / ‘the slave’) through its endowment with (non)value. I’m speaking of the seperatability as a western ideology.

Igor Kopytoff analyses the process of commoditisation – already premised on an anterior objectification – as a process of becoming, which conversely implies the potential to de-commodify an object by taking it out of the economic sphere. Understanding its status not as given but made, thus as historically specific, he stumbles upon a contradiction, which unfolds its full paradoxicality in the context of art. Commodification intentioned for exchange requires not only the homogenisation of value for the sake of a wider exchange – confining the heterogeneous – it also presupposes the cultural process of defining the non-commodity. With reference to Durkheim, Kopytoff identifies the apparent need of a society to keep a specific amount of its surroundings heterogeneous, singularised as non-commodity, to function as society’s collectively shared ‘symbolic inventory.’5 Its being a non-commodity is the effect of discourses (moral/aesthetic/religious), supposedly outside an abstract economic sphere, which it actually shapes and by which it is being shaped alike. A reciprocal process, conceivable in its simultaneity alone. An interdependency blatantly expressed in the realm of art, which still cloaks its production of value – saturated by asymmetrical power relations – with the myth of the artwork as possessing an inherent value in itself. “A Picasso, though possessing a monetary value, is priceless in another, higher scheme. […] But in a pluralistic society, the “objective” pricelessness of the Picasso can only be unambiguously confirmed to us by its immense market price. Yet, the pricelessness still makes the Picasso in some sense more valuable than the pile of dollars it can fetch […].”6 The Picasso thus obtains value in these simultaneous interdependent processes, which solely can be differentiated and split artificially into a cultural and an economic value, if one constructs their spheres as separated.

In order to refute this binary thinking, as a discriminatory form of representation originating in the colonial encounter and organising our thought-system into oppositions still today, like freedom and bondage, the inside and outside, past and present – always marked with an implicit hierarchy — one has to follow Stuart Hall’s call for a re-reading, for a re-narrativzation of this violently Eurocentric, linear, (neo)colonial perspective.7 “The very notion of an autonomous, self-produced and self-identical cultural identity, like that of a self-sufficient economy or absolutely sovereign polity, had in fact to be discursively constructed in and through ‘the Other’, through a system of similarities and differences, through the play of difference and the tendency of these fixed signifiers to float, to go ‘on the slide’.”8 (Stuart Hall). It’s a plea for an inevitable transcultural, transnational and transdisciplinary perspective – in favor of the hybrid. It’s the plea of this essay!

Picasso, like Le Corbusier.

2020

London

A day in January

Pacotille. Slavery’s abject invention. A ‘slave’s’ value. It’s expression. Metonymy. Pacotille: an object. Here,in its clarity? in front of us: Glass beads, brass manillas (fig.2).

Image Credits: Imke Felicitas Gerhardt

Grand boulevard. Vanishing point: Buckingham Palace, Westminster London. 12 Carlton House Terrace, Crown Land, Crown Estate, the Monarch. Institute of Contemporary Arts. Continuities. “[…] citizens of European nation states are most certainly affected, and shaped in ways that are not particularly visible to many people it seems, by the legacies of colonialism and slavery that continue right into the present. And these are not just “affective legacies” but are material to their core.” (Brenna Bhandar).9

Property. This universalised and naturalised concept, to order the world, to shape the relations in(dependence) to ownership. Premised on reification, commoditisation and abstraction, this internalised matter of course is simultaneously describing a historical process, which enabled a transnational capitalism to emerge — throughslavery and colonialism, through making the slave an exploitable commodity, through appropriating, commoditising and exhausting colonised land, declared asres nullius — and at the same time, in its ongoing dominance, it’s the fundament of a western system of thought, it’s a naturalised way of understanding, explaining and representing the world. Continuities. Inscribed — like traces in the commoditised object, appropriated, property, in migration.

Pacotille, french for ‘rubbish.’ Rubbish, like valueless. One dimensional currency. In Cameron Rowland’s seminal exhibition 3 & 4 Will. IV c.73 in Londons Institute for Contemporary Arts (ICA), January – April 2020, one sees the Pacotille lying on the floor — position 3.10

A delicate chain, strung with white glass beads and grey brass manillas. Unobtrusive, its presence, blending with the grey floor, where it gets lost, overlooked, quickly measured in its appearance just. Just an object in its clarity, like the Exterior Light in concrete by Le Corbusier. This Pacotille, worth a slave life, maybe.

In the essay The racial thing. On Appropriation, Black Studies, and Thingliness, published in Texte zur Kunst[Issue: Property 2020] David Lloyd challenges the prevalent superficial cognition of the ‘object’ as just given, just there, like the subject too, who captures it. This naturalised split — broadly criticised already in Black Studies by raising awareness to those millions of silenced voices, bereft of their subjecthood and violently degraded to an exploitable objecthood, from slavery to Apartheid, or further (“[…] the colonial lives in its after-effects […].” Stuart Hall11 — is Lloyds point of origin from where he goes on to dive into its complexity. “For any thing to be reified, it must already have become an object, whether as an object in exchange or an object of the law, or an object subject to the epistemological violence of representation. It must, paradoxically, have ceased to be a thing.”12 Referring to Hegel and in the same second impugning him, Lloyd describes the process of a thing becoming an object, where the immediacy of the former – presenting itself to the senses in its here and now (Hegel) – is transcended through its translation into a concept, through its transformation into an object for representation. In a dialectical process this objectification becomes the condition for subjectification to take place. It enables man to realise himself as an autonomous subject through the repulsion of the object as his antithesis, through its appropriation in becoming “[…] an object for him […].” (Hegel).13

Autonomous subject. To become a subject. This empowering transformation — so imperceptible. For those, who are not perceiving the scars of objectification on their skins.

When objectification – of a thing, of a person – always implicates the violence of being represented, of being appropriated – whether for the sake of epistemological dominance or – and this is interdependent – for its economical mastery by voraciously turning things into commodities to extract and exchange value – is it then possible – and this is Lloyd’s ingenious idea – to think the thing anew, to conceptualise it as a residue of resistance, as “[…] not-yet subsumed into representation as a value.”14

Starting with Hegel’s definition, which understands the thing as pre-reflexive and pre-determined, as not being translated into a coherent concept – hence object yet, Lloyd however differs clearly from the latter in his positive interpretation of the thing by disclosing its potential for resistance, located exactly in its pre-determinacy. If the thing in its status of being non-defined harbors a multiplicity of properties, which are violently negated by its objectification for the sake of representing, appropriating and exchanging it — isn’t then the revelation of its multiplicity, the fracturing of its assumed coherence in appearance — its liberation?15

Pacotille. A delicate chain, strung with white glass beads and grey brass manillas. Unobtrusive, its presence, blending with the grey floor, where it gets lost, overlooked, quickly measured in its appearance just. Just an object in its clarity, like the Exterior Light in concrete by Le Corbusier. This Pacotille, worth a slave life, maybe.

Reverse. How to fracture the outer coherence, allowing its differences to occur? How to grasp the multiplicity inits unity? — How to think outside the episteme (Foucault) which in producing the object’s oneness defines the horizon of the seeable and speakable?

Less a surgical intervention to extract its inner parts by cutting the opaque – infinitesimally – it’s rather the attempt to overcome its constructed duality entirely, and in doing so denying the supposed neutrality, or let’s speak in the pathos of Le Corbusier, the universality of the pure form. It’s rejecting the myth of formal objectivity by uncovering its unheeded presence in time, its traces of circulation, its violent fissures received in migration. Object biography.

1760

London

A day in July

“Pacotille was the name for the category of goods made for the trade of slaves, which carried nearly no value in Europe.”16 – but 100% profit – then. – Now, in the ICA? Lying there, on Crown Land. „Abolition preserved theproperty established by slavery. This property is maintained in the market and the state.”17

Manufactured in 18th century Europe, these brass manillas and glass beads traveled the world. Connecting the formerly unconnected and dividing it. Carrying the division of the globe in its two-fold character, in its dual existence as (non)value, in its being as a one dimensional currency. Valueless in Europe – rubbish- they were used to buy slaves in the overseas.

Oversea they crossed. These Pacotilles, like a joining separation of the continents. A division, which they actually set in place, incessantly. A separation or polarisation (re)produced by its change in value. The invention of an Inside and outside, here: the West and its rest. Civilisation and its supposedly degenerated Other. An ideological construction working through opposition. And then purifying the opposed. Exclusivity. Denying its interdependency, its hybridity. Denying that the rise of capitalism is based on the rise of slavery, that progress rested upon enforced stagnation, that western modernity is predicated upon exploitation, that our liberal understanding of freedom is grounded in bondage. The traveling object carries the history of this ideology into the present and nourishes it. These Pacotilles, or this Exterior Light, plundered from a symbol of independence. To give and receive value – this western prerogative. Continuities. A prerogative that also has the power to determine what is an object and what is a subject in the first place. Or let’s put it differently, regarding its processual character — what, or who is made into an object for the sake of extracting value and who is allowed to become a valued subject.

The Barbados slave act from 1672 determines the ‘slave’ doubly. As simultaneously being a chattel – a moveable property – and as being an immoveable property alike – chained to the plantation as an integral part of the real estate, or let’s say, as a commoditised part of a newly commoditised land.18 Again an object in migration. And then in stagnation. Again a dual inscription with value to thoroughly construct and cement this ideological division which bears the Other in the first place. To deepen that fracture, to naturalise it, internalise it as western self-conception. The ‘slave’ and ‘its’ dual value. Being at once defined as non-person without – and determined to be an object with or of – value – surplus value – to exploit. A dual inscription violently enforced by the West, in dependency to it. Codependency. To make the slave an object there, is to have its value here. To appropriate, commoditise and exploit land outside is to flourish the land inside – allowing ‘modernity’ to occur. To enable progress here is to enforce stagnation there. To morally rise above the ‘savage Other’ is to deny the construction of my own identity. The refusal of cultural entanglement equals the white-washing of economic interdependency. Or the other way around. Its inseparability – traceable in the materiality of the ‘object’ – the befallen violence – expressed in its (non)value – given.

Marx once famously said: “[…] capital is not a thing, but a social relation between persons which is mediated through things.”19

In this regard, Gyan Prakash aptly asserts:“[…], the history of unfreedom is the history of capital in disguise.”20

2,000,000 enslaved people, shipped in the 17th century from Africa to America.21 Creating social relations, creating capital — being violently mediated and its mediator alike. They became objects in circulation. Their value extracted for circulation. And accumulation — in the West. Their being, made abstract to let the abstract arise. Capitalism anchors its genesis, similar to another Western dogma, in trinity. Triangular trade. Its synthesis — abstraction. God or Capital. Metonymy.

“Eric Williams describes the triangular trade as providing a ‘triple stimulus to British industry’ through the export of British goods, manufactured for the purchasing of slaves, the processing of raw materials grown by slaves, and the formation of new colonial markets for British-made goods. ‘By 1750 there was hardly a trading or a manufacturing town in England which was not in some way connected with the triangular or direct colonialtrade’.” (Cameron Rowland).22

The doctrine of the trinity in Christianity is based on a paradoxical simultaneity. A differentiation of its components and their indissoluble unity at once. God in the middle is the synthesised abstraction of his differentiated parts. Capital in the middle is the synthesised abstraction of its discriminated parts. Or in other words, industrialisation is not Slave Trade, it is not Colonialism – but Capital, like God is every single one and its unity. Whereas the Christian God precedes his parts in which he finds his expression, capital and capitalism as its attendant social order, could – on the contrary – just develop as its all-encompassing middle, through the closing of the triangle, which brought its middle into existence. Triangular trade. The middle – Capital – is thus the abstraction of the real. Is abstracting the real into real estates, real properties, real value through real dispossession, real appropriation, real violence. As soon as Capitalism came into being, hence, from a historical perspective, when the triangle closed (triangular trade), it assisted in every single part and became simultaneously expression of its abstract whole. This abstract whole, incessantly fed on the depletion of the real, whose abstract substitution it became, got continually broadened by voracity. The need to accumulate in the center forces its sides to expand. Expansion. Continuities.

Let’s quote Marx another time: “The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of an indigenous population of that continent, the beginnings of the conquest and plunder of India, and the conversion of Africa into a preserve of the commercial hunting of [blackskins], are all things which characterize the dawn of the era of capitalist production.”23 It is the dawn of something abstract, more abstract than a (transatlantic) division of labour, it’s the beginning of finance capitalism. Its the foundation of the banking market — former slave traders turned into powerful banking houses – such as Barclays — it’s the establishment of an abstract Creditsystem — which according to Marx could just develop in symbiotic relation with colonialism24 — its the onset of an abstract and violently asymmetrical play with value. Retracing the development of Capital means retracing its conditioning parts, it means retracing its lines of connection, or to stay with the picture of the triangle, retracing the routes of triangular trade. Traces to be found in the circulating ‘object’ on which they got imprinted. This needs a going beyond the ‘object in its clarity in front of us’, to follow its objectification in time, the process of its becoming an object for – appropriation – circulation – exploitation. To thereby understand its changes in value is to ‘open it up’ with the hope for resistance to occur.

1760

Anomabu

A day in August

Pacotille. Here: these brass manillas manufactured in Birmingham and these glass beads produced in Venice. Declared rubbish. The production of rubbish – of non-value for value. Transforming its outside from where it gets defined. Flourishing or withering it. A reciprocal process, boosting the production in the West, stimulating it’s industrialisation — to then ship it to Africa, heavily loaded with an invisible ideological burden, to let a continent decrease. “British trade in West Africa was understood to be nearly 100% profit.”25 A connection found in division. The passage — the formation of land, like the formation of the Other – the arriving. This Pacotille – it changes value – now being a little change for exchange – in exchange – a human life.

Reading Marx, Capital is stated as a social relation, and so value, a social construct. If not intrinsic, not a natural quality, what then is defining a commodity’s value? For Marx, the latter is to be found in its exchange value, expressed in turn in its market value, hence its price. Two commodities can be exchanged based on a specific exchange ratio, which is grounded in the assumption that they have something in common. That means that a barter – allowing five pieces of this to equal two pieces of that (exchange ratio) – requires a third, that which makes it equatable. For Marx, this third is labour (labour theory). It’s the question of what is the average time needed to produce a specific commodity. If the invested average labour time thus defines a commodity’s exchange value, which is expressed in its market price — profit can only be attained by producing below the expected time and simultaneously reducing the costs of production, which are understood to be the raw materials, the wages of the worker and the means of production needed. Marx sees the gain of profit primarily enabled by the exploitation of the worker, which is mainly expressed in the wages he/she receives. Regarding that labour power is itself recognised to be acommodity, it becomes the question of how much is needed for its (re)production, that means how little can the wage be to still keep the worker – the labour power – sustained. 26 That’s said, wages were often held at a moderate level, or at least at one slightly beyond the securing of existential needs, allowing capitalism – with a partly content workforce and a healthy consumer demand – to flourish.

Indeed, while the exploitation of the worker in the West was horrendous, the super-exploitation Capitalism caused everywhere else, in its supposedly detached ‘outside’, needs to be scrutinised. Shreeram Krishnaswami depicts the potential provided by slave trade and colonialism for a drastic reduce of the costs of production, causing therefore a surreal discrepancy between the investment and its profitable outcome: “Thus under colonialism, the overall rate of exploitation could be increased substantially by using slave labour with its almost infinite rate of exploitation – or super-exploited labour in the colonies, whilst keeping the rate of exploitation constant in the core or even allowing it to decrease (i.e., allowing real wages to increase). Furthermore, capital costs (C) include costs of raw materials used in production. The cost of raw materials-extracted primarily in the colonies- was kept to a minimum by the colonial powers.”27

Pacotille. The perfect commodity? — Solely produced for the sake of making profit in exchange. Is it the purest expression of the capitalist logic of maximisation, which it itself enables to come into being – in the West – in its distorted libertarian face? Pacotilles — they are at least the purest expression that the emergence of a capitalist logic, of Capitalism, is not explicable in economic terms alone. Their paradoxical double inscription with value shows that the economic and cultural discourses are hybrid in their core. It’s this integrated existence which then allows in turn to disclaim the dependence on the Other, who is constructed in his denial. What is simply meant here: If one would just follow an economic definition, then the Pacotille – having no exchange value- would be valueless. If one combines an economic understanding with a cultural — one would assume that an economic logic is overlaid with a racist cultural logic, or the other way around, but would still imagine the discourses to be separated – just interconnected. But being so deeply engrained into each other, they are in fact inseparable. The economic logic is the cultural logic, because the way it came into being and the way it works is inherently racist and sexist.

The Pacotille in its worthlessness is exchanged with a commodified being, a ‘slave’, which in a racist capitalist logic, equals the Pacotille in its valuelessness. A fair barter. Simultaneously and paradoxically this worthless rubbish is becoming value in the moment of exchange. Or rather – in the moment of exchange it is of value for – not the one who receives it – but for the one who gave it away. However this seems equally imprecise due to its assertion that there is an immediate release of value. Infused with a racist logic, which classifies the commodity received – the ‘slave’ – as equally valueless, a fact in turn expressed in its status as a commodity – this exchange can’t be seen as releasing any direct value. If it would release a direct value, then this would be expressed by, in turn, value, given to and therefore be seen in at least one of the commodities in exchange. Rather it is an indirect, a postponed value, not yet there — not present in the exchange in Africa – neither fully on the plantation in America, where the ‘slave’, for which the Pacotille got exchanged is brought — but soon in its entirety to come. It exists and continually grows in imagination —taking shape in the assumption of a profit in the future. It is a value not given to the ‘object’ (the former Pacotille — now the enslaved person) but just extracted from it. It is a coming into existence through destroying the Other’s existence, from which it derives. No-thing in itself — just in some-thing — a value always in conversion – now converted for its homecoming. Circulating in the shape of its temporary carrier, which is granted no value in itself, the Pacotille first, the commodified body later, it can, after coming back from this long journey, finally realise and materialise itself in (the) Capital. Grand boulevard. Vanishing point: Buckingham Palace, Westminster London. 12 Carlton House Terrace, Crown Land, Crown Estate, the Monarch. Institute of Contemporary Arts. The Pacotille, now lying in the ICA, is surrounded by its value, which was already there 260 years before itself.

Rewind. Pacotille, these brass manillas, these glass beads strung on a delicate chain — exchanged for another ‘object’ in chains. Global value-added chain. To add to, like to build up. To build up, like to increase. To increase like to enlarge or to expand or to spread. To add, like to accumulate. It’s the triangle’s coming into being, successively growing with the collected sum in its middle.

However, the synonyms which expresses its becoming can be replaced by their antonyms.

To subtract, like to take from. To take from, like to decrease. To decrease like to shrink, or to diminish, or to lessen. To accumulate can be replaced with to scatter, to divide, or to disperse.

Bodies and their land.

1760

Barbados

A day in October

The objectified and commodified ‘slave’ gets violently dispossessed from his/her body, from his/her land to be made possess-able. Being a chattel in transit, he/she becomes fixated property on the ground.

Property — this two-faced expression of liberty, concealing its hypocrisy with Enlightenment’s permission. Hiding its feint, behind the authority of the civilised white man and his interpretation of property as the embodiment of ones freedom. The idea of property as a basic right – hegemonised – internalised – anchored in the constitutions of these forward-thinking societies and in the minds of its members. – To own – this basic right, based in exclusivity, but shining universally, one has to be a subject. One has to be allowed to become a subject and then to become a citizen, a legal body. The idea of the free thinking, autonomous subject, endowed with the basic right ‘to own’, in which his liberty gets expressed, was/is the sole right of the white man. To own anything starts with owning ones body. A matter of course denied to all women, all people of colour, all – outside a heteronormative spectrum, a matter of course, denied to the majority of humankind. Property – Its dominance as an internalised and naturalised understanding of the world and of the self in relation to it, its dispersion worldwide, illustrates nothing else than the economic and cultural dominance of the white man in its simultaneity. The idea of property, through which we structure the world today develops in concurrence with the historical formation of colonialism and slavery.28 The way we conceptualise the self-contained subject as well as our self-conception as a culture is based on the latter. John Locke’s Two treatises of Government (1689) with its seminal claim for private property, generally understood to be the foundation of liberal democracy and capitalism, should obviously less be treated as its origin than as already influenced by – and as the legitimising update of – a proto-capitalism and its appropriation and colonisation of land in the Americas. His ideas of a liberal democracy thus of the subject, developed under- and are embedded in the impression of slavery. (Locke himself was amongst other things: Secretary to the Council of Trade and Plantations 1673-74 / member of the Board of Trade 1696-1700 / shareholder in the (slaveholding) Bahama Adventurers).29

Locke’s conceptualisation of private property as a natural right is premised on self-ownership, that means owning ones body. By working the land, which is formerly communal, man puts something of himself (of his own property) into the land and is thereby entitled to own it. To justify the appropriation of indigenous land in America as righteous, Locke argues that uncultivated land is valueless and only becomes of value through the achievement of farmers, to whom it therefore belongs.30

This notion of being ‘entitled’ to claim a land as ones own, is not only expression of an initiating ‘commoditised vision of land’ as Brenna Bhandar puts it, but also of colonialism’s ‘racial logic of abstraction’, which denies indigenous people – , or makes it bureaucratically nearly impossible for them to register for (their) land.31 “Property law is one of the central motor forces of colonialism. As one of the primary means of seizing and asserting ownership over the land base of another people, property law was used to fundamentally transform the use and control of land and resources, and with that, the social relations, economies, and cultural practices that were imbricated with indigenous and existing forms of land use.”(Brenna Bhandar).32

The enslaved person, the chattel, shipped from Africa, arrives in America. Dispossessed from his land – and his culture – suppressed – like his body – maltreated – to cultivate – land – of someone else – dispossessed from his land – and his culture – suppressed – like his body – maltreated.

The objectified and commodified slave – the objectified and commodified land of the indigenous people became synonymous. An involuntary bond in bondage. “Colonized land and enslaved labor were made interdependent.”33 Both appropriated, they became the condition, the integral part of a plantation’s value. To be part of a plantations value meant to be part of its exchange value. The exchange value increased – as the costs of production decreased. This is witnessed in the West in the ongoing balancing act of weighing up wage rates against labour power. The civilised twin of balancing or weighing up which torture method, or how much violence is ‘within reason’, to still guarantee efficiency. “The plantation’s value was determined in part by the efficacy of its confinement.”34 The ‘slave’, this dehumanised objectified being, with ‘its’ twofold inscription of value. Treated as a non-person his/her value is denied and simultaneously, because abased to be a property, he is in many respects of value for his owner: Being of no- value, hence of value – regarding that the former legitimizes unlimited exploitability – means being of value to indefinitely produce value to be extracted. ‘Released’ of the slave to be accumulated in the abstract center, it is creating Capital in the capital, bearing capitalism. The ‘slave’ and ‘its’ paradoxical status of non(value) shapes the core in directly two lasting regards, firstly enabling (the) Capital’s beautiful facade, its display of wealth and secondly it is the condition for the invention of its organism. The enslaved person is again of value because of his/her use as collateral, as mortgage for a plantation, financed by credit. Colonialism and slavery, by being the premise for capitalism to occur, are therefore the testing ground and the first embodiment of its central features: credit and debt. The explosion of banking houses in Great Britain, 12 banks in 1750 – 668 banks in 1800, are one expression of the fact that the whole plantation system in the 18th century was based on credit, which as a system thereby came into being.35 The plantation and its value, the way it cultivates value is the integral part of the abstract whole in formation. Capital, like God. To finally close the triangle, to become total in being its parts, it’s time for the sending of the Holy Spirit, to bring the word of God into the entire world.

Plantation, this depletion of nature by starting to cultivate in excessive monocultures (Climate Change). Continuities. This depletion of bodies for profit. The gambling with it. Continuities Creditsystem, this naturalised abstraction, a matter of course. These grand scale speculations, these bursting bubbles (2008). Continuities. The slave as mortgage for the debt of the plantation’s owner means: the plantation is the ‘slave’, Capital is the plantation, the ‘slave’ is nothing but its core.

“Plantation mortgages exemplify the ways in which the value of the enslaved, the land they were forced to labor on, and the houses they were forced to maintain were mutually constitutive. The enslaved simultaneously functioned as collateral for the debt of their masters while laboring intergenerationally under this debt.”36

300 years later, debt is the imprisonment of the individual. It’s the confinement of the collective in abstraction. Debt, this invisible haunter. Its presence in the subliminal is the reality of life of the English citizen. Debt and guilt, in German they are used synonymously (Schuld). — Spirits that I’ve cited, my commands ignore [Die Geister die ich rief, werd ich nun nicht mehr los] (J.W. Goethe).

2010

London

A day in September

Concrete. Le Corbusier’s most desired material, or Modernity’s most desired material, or its expression. Metonymy.

Concrete: an object. Here, in its clarity, in front of us: An Exterior Light, £26,250.

Like nervous flies, pulled towards the light. Here by desire, too. Fraught faces of bidders buzzing in speculation. An object, its price. Its value — in the future. An auction, this exciting and delightful pricing of an object – it’s evalueation. A gamble with the imaginable – a fathoming of contingencies – a pushing of limits. Finding potency in potentiality. Potential profit – a fast- selling-item. This auction, it spreads the charm of the arbitrary — like power does. A former power, so used to its monopoly over the colonial markets, over the pricing of goods which went there. Now, presenting itself in less absolutist airs, unforced and free, this free market, with its monopoly to set the price for the colony’s independence. Corbusier’s Exterior Light made for Chandigarh. The simultaneity of assessing value and determining it. Like an inscription from the outside, but one which gets re-essentialised, re-embedded into the object, as if it’s just aninnocent affirmation of its inner value which was already there. This romanticisation of the purity of the object, this inner truth of Le Corbusier’s piece of concrete. An attested universal truth.

Given the inseparatibility, or hybridity of the cultural and economic sphere, which is laying bare in the act of pricing, as a quantitative expression of (cultural) value, the price for the Exterior Light from Chandigarh expresses either a paradox, or simply a continuity. Again, if cultural significance is implicit in an object’s price, how do we explain that this Exterior Light from Chandigarh, a city, planned under the aegis of Le Corbusier, as India’s symbol of independence, as their monument of modernity, is of no value in India, but is gaining high sums, labeled as monument of modernity in the West? The lamp substitutes Chandigarh – Chandigarh substitutes modernity. Corbusier, the substitution of both. Monument derives from the Latin word monere – reminding -remembering. A monumentalised memorandum. A collective symbol, a shared sign – whose significance? Whose modernity? Whose monument? Whose value? Whose belonging? Whose independence? India has another symbol for the latter. A symbol capable of both: remembering the word’s root, and proudly visualising and realizing its prefix. Less concrete heaviness rather waving lightness. Less abstract rather hands in motion. Less intellectualised rather lived. Less planned rather organically grown. It’s the national flag, it’s the Charkha on the national flag. It’s about its coming into being. A nation coming into being. A vision of the collective, not simply for the collective. An idea of a nation, before a nation.37 1921, 26 years before the latter’s foundation (1947), it becomes India’s inofficial flag, chosen by India’s National Congress38, which, established in 1885 as an elitist project to lead the country to independence, becomes a mass movement around that time.39 Charkha, the spinning wheel, the important symbol on the symbol.

Coincidentally this emblem is similarly metonymic with an authority figure like Chandigarh is. Gandhi and Le Corbusier. If for the latter Chandigarh as a whole, as well as the material (concrete) and the Modulor system, which he invented and applied there, are expressions of his prophetic vision, a higher, universal truth laying bare40 — then Gandhi’s invention of the Satyagraha, a Sanskrit neologism, translatable as truth-force, practiced as a form of passive resistance or civil disobedience against the British oppressor, is equally prominently expressed through a symbol, through the Charkha, the spinning wheel. Satyagraha, two of its many rules are non possession and Swadeshi, an economic strategy implying, amongst other things, the boycott of imported goods.41 The spinning wheel, a symbol for independence and at the same time its condition, its driving force. Spinning, its continuousness, this processing of time and place, this golden thread, slowly covering the dependent body in self-sufficiency. The spinning wheel, a symbol being present participle and future perfect in one. Independence, the formation of a nation, not an event in a linear story, like the 15.08.1947 suggests, less hierarchical, not top-down, but a horizontal becoming, imagined in a form of dissemiNation, as Homi Bhabha terms it. A self-generating process, the rise of a national consciousness through a narrative performance,42 like spinning a thread and then weaving a dress to become a symbol, carried through streets, like the embodiment of an idea, like the making and materialisation of a consciousness, searched and found in symbolic unity. Non possession and swadeshi, two rules, inseparable. A western understanding of the world and of the subject – its boycott – through the boycott of the formers materialised presence in the world. Independence. To reclaim land, dis-possessed is to reclaim a dis-possessed body. Not in the sense of a re-possession as this would be just an exchange of prefixes by keeping an underlying structure, which only allowed land and bodies to be commodified possessions in the first place, but rather an attempt to dissolve an economic structure together with its cultural implementation. A capitalistic structure, which not only disintegrates a land and its people, but by doing so, divides the world. Exploiting the former, keeping them stagnant, to let the West – in supposed autonomy – dynamically progress, thereby materially and ideologically widening the split to the Other, who is simultaneously constructed. The principles of Non possession and Swadeshi question a doctrine of faith, based on a concept of trinity. They question a triangular trade and its abstract God, Capital. The spinning wheel as the visual expression of these principles, their symbol and the prerequisite of theirrealisation, gains its vigour from its capability to allow the prefix to come into being and to refer to its root at the same time. Cotton is the embodiment of India’s violent dependence and of its liberation alike. Cotton is the embodiment of the triangular trade. Shreeram Krishnaswami calls cotton the link between capitalist and underdeveloped countries,43 or rather one should call it the connective of their mutual coming into being in opposition. A brief illustration with historical facts: Between 1780 and 1840, cotton, or rather the cotton industry became the main stimulus for industrialisation in England. Thereby systematically corroding India’s existing cotton industry, by inhibiting India’s export through untenable taxation, partly destroying its cotton factories by military force and simultaneously exempting only British goods from import taxes in India.44 “Not only did the colonies provide cheap raw cotton through the exploitation of slave labour, but the colonies also provided 90 per cent of the market for finished cotton goods.”.45To phrase it differently: The exploitation of raw materials in the colonies through the super-exploitation of enslaved people, then shipped to England to be processed, is one of the two conditions for industrialisation. The other is to bring these materials back to its country of origin, enclosed in manufactured goods, which not only provided unimaginable profit rates, increased by England’s monopoly over the pricing of these goods, but also kept India’s economy dependent and stagnant, preventing any broad development to take place.

The Other, this integral part of the western-self. It’s separated, alienated and denied constituent. Nourished by the schism so engrained in its being. It forms the western identity, which can only imagine itself as free through the distinction to the Other, the denied half of itself. The dependency of its being, sustained by its suppressed part, needs to be negated to oneself – in fear of losing integrity, alongside needing to be loudly repudiated to the outside. This dependency is incessantly combated with the proclamation of ones own superiority, which finds its expression, and sought affirmation, in a material supremacy, being itself the result and the ongoing driving force in the destruction of the Other. It’s this feeling of cultural superiority, which is the spawn of the latter and its legitimisation. It’s the elevation over the inferior Other, over this inferior part of the self, turned inside out. This fear and this hate towards the allegedly alien in oneself, in ones culture, this conjuring of the purity of the latter’s origin is product and producer of a simultaneously emerging capitalism and colonialism together with its enlightened foundation in its unity. To deny the condition of my own identity, to negate the exploitation of the Other as part of my existence, is to turn this inner opposition inside out. It is the need to think in outside oppositions, to be able to deny ones own moral turpitude. The suppressed inferiority of the enlightened self. Eugene Genovese writes: “The power of slavery as a cultural myth in modern societies derives from its antithetical relationship to the hegemonic ideology of bourgeois social relations of production.”46

And Gyan Prakash – by analysing the West’s need to hide the conditions of its development in a constructed dichotomy, allowing to ground its self-conception in exclusivity, its exclusive achievement of free labour, the free subject or modernity, and other cultures as backward in opposition – states: “Such a naturalization of free labour conceals capitalism’s role in constituting bondage as a condition defined in relation to itself, and presents servitude as a condition outside its field of operation, as a form of social existence identifiable and analysable as alien and opposed to capitalism.”47 Slavery, although being the condition for capitalism to develop as a success story in the West, becomes the morally denied Other. Enveloped in a linear narrative of progress, economically, as well as culturally, the West — thereby also writing the narrative of the Other in dependence — promises now civilisation through assimilation. This white man’s burden. Indeed, Britain’s abolition of slavery, 1833, is for Saidiya Hartman therefore a non-event: “The entanglement of slavery and freedom trouble facile notions of progress that endeavor to erect absolute distinctions between bondage and liberty.”48 An economic progress, which required exploitation. A subjectification which asked for objectification. A conceptualisation of property, of liberty, which is the resultof the dispossession of the Other. The violence of Capitalism’s coming into being and the violence of its persistence, is denied by its discourse of freedom, humanity and civilisation.

It’s biggest pretender – the creditsystem – this value accumulation out of the abstract. Creating this illusive freedom to possess, to own, which is actually based in unfreedom, in dependence. It’s not a direct possession, it’s indirect dispossession.

In the beginning of the creditsystem this was surely more violently clear: the financing of the plantations through credit, a possession based on the dispossession of the enslaved person, its body, which becomes the guarantee of its liquidity. A possession based on the dispossession of land. Property derives from appropriation. This fetish of ownership. Responsible for the distribution of a land and its social relations on it – in the past and in the present. Nearly everywhere. For post-abolition India, Gyan Prakash explains how the British in their ‘civilising mission’ modified, or reformed the caste system, which they morally condemned as embodiment of unfreedom, as classifying people and keeping them in a violent relationship of dependency to each other. Conceptualised as freedom’s Other, as liberty’s opposition, discursively negating its interdependency, the British, by feeling once more legitimised to civilise, do so by just translating the dependencies of the caste system, by literally just displacing them into a more abstract realm. Former intergenerational dependencies, partly dissolved, allow new dependencies to rise. A differently conceptualised dependency, a contractual, a legal dependency. Prakash speaks of a successive transformation through the objectification of labour relations in things and the establishment of an idea of private property. This goes together with the emergence of a land market and the commercialisation of agriculture.49 “The objectification of social relationships in land […],”50 entails the reordering of the former social hierarchy due to ownership, that means altering established identities as well as their uncommodified relation to the land. A new legal system of ownership based on loans. It’s not the master forcing the objectified slave to work a land which is not his own, like his body is not his own. It’s not the master’s debt which requires the Others lifelong exploitation. Instead it’sthe establishment of an understanding of being through owning, that now forces to work under ones own debt. Inabstract dependence to the abstract. Voluntary servitude or debt bondage, as Prakash calls it.51 Like an individualisation of dependency, a micro-dependency embedded in macro-dependencies, where the former is the offspring of the latter carrying forth and preserving its legacy. Being dependent on the abstract, which is in turn dependent on dependencies. An interdependency in asymmetry. In violence. If Capital’s formation and longevity is dependent on the borrowings of the plantation owner, on his indebtedness, then the master’s solvency is dependent on the ‘slave’. The ‘slave’ in turn is paying these dependencies — which are not only the condition for accumulation to occur, but its life-extending measure at the same time — with his/her life. His/Her objectified body, is a usable part in an accumulation-machinery, which, though successively sucking in everyone and everything into a relation of interdependency, can only run on full power, when these dependencies, on which it is itself dependent, are based in asymmetry. A hierarchy, which is not just expressing who is owning more and who less, but who is allowed to become a valued subject and who is not in the first place.

Like the master is dependent on the slave in his solvency, so the Empire is on its colonies. So civilised in this past-abolition 20th century, it is still a solvency not just paid with money, but with bodies alike. In the second World War, India was not only enforced to sacrifice its people for the Crown, but also its money. “[…] the United Kingdom ended the Second World War with a debt to India of £1,300 million, an amount equivalent to almost half the country’s GNP. After 1945 […], Britain’s continued solvency hinged to a very large extent on the negotiation of a satisfactory political settlement with its Indian creditors.” (Ian Copland).52 The post in post-abolition apparently doesn’t mean past-abolition, like postcolonialism signifies the continuance of its root. Sometimes these dependencies – which accumulate in the abstract, where they hide behind this big banner of freedom, the free market, the free subject – become visible. Sometimes when the gambling with them becomes to big, sometimes when the speculation over their value fails, then these abstract bubbles, saturated with dependencies, start to burst. Often at first in Capital’s capitals, thus in the West, but because of its global interdependence, they burst and causing pain everywhere.

1953

Chandigarh

A day in December

Independence. Chandigarh as the symbol of in dependence? An event in a continuum? A proclaimed new identityin imported forms? Visions which carry in their articulations the entanglements of the past.

Independence. This desire for a rupture in built continuities. Continuing infrastructure, road systems, maps, revenue records, architecture, court procedures, administrative institutions, political forms, economic trade. The continuing syntax of a language.53

Chandigarh, this planned new city, this planned rupture, this implemented continuity. — In continuity, the spinning of the Charkha, this performance of a tradition, this processualised detachment. Frantz Fanon once said: “To educate the masses politically is to make the totality of the nation a reality to each citizen. It is to make the history of the nation part of the personal experience of each of its citizens.”54 Without wanting to question the concept of the nation in this moment — as itself a western notion, occurring at a specific historical moment in time and saturated with an understanding of possession, a sense of cultural purity,— Fanon’s emphasis on personal experience, on a nation’s realisation in concreteness, instead of imported concrete, seems nevertheless relevant. Disregarding the figure of Gandhi himself and his romanticisation of a living in autarky and simplicity, it seems yet obvious that the long-time inclusion, his mobilisation of the masses, their arising awareness of a shared pain, the rising of a self-awareness, is exactly Fanon’s individualised realisation of the nation. It is this self-spun image, a roughly spun narrative, connecting hands and ideas, connecting the individual with its community. This self- and collectively spun thread, not a rupture, but a link between ones history and future. It’s the omnipresence of the spinning-wheel, its ability to concretise an idea, make it tangible in ones hand and sensed on ones body, which carries it out. It is something abstract becoming concrete, not abstraction in concrete. Chandigarh.

“Let this be a new city, unfettered by the traditions of the past, a symbol of the nation’s faith in the future.” (Jawaharlal Nehru- India’s first prime minister).55 A symbol, pre-loaded. Like representation is a substantive and not a verb. So concrete, that it is universal. Le Corbusier’s vision. A vision exterior. His Exterior Light is shining into the void. Chandigarh. Built in a void. Of a partition, filled with violence, the lost unity of a desired identity. Ethnic violence, more than one million deaths, 13 million refugees, more than 88 million people directly affected.56 India’s and Pakistan’s coming into being in the moment of their separation. To divide and rule, Britain’s ingenious strategy in the colonies. The partition, their generous farewell gift. Gandhi the father figure, assassinated. The masses, divided. They’re joining clothing, unseamed. The thread, lost.

Nehru. Another man, another vision. Or a desire. Shared, by another man, with another vision, Le Corbusier. Their power to see, their wisdom to plan — a future — in a Five-years plan and a planned City. A vision, emanating from the subject. A new beginning, a new day.

“At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends […].” (Nehru – Independence speech).57 A-voided we. A void — that is on what Chandigarh was built. The void after a separation. And Chandigarh the substitution for its loss. When India and Pakistan were divided, Punjabwas, too. Lahore, its cultural Capital was from then on belonging to Pakistan.58 Chandigarh, thus, built into this vacancy as its replacement. A substitution for the collective we. Or for the new. This fetish of the new and of progress. Yesterday’s stagnancy. Time in linearity. A colonial discourse. Backward and forward – this internalised axis. Internalised humiliation. Inferiority complex (Frantz Fanon). Which maybe roughly expresses itself like that: “Everything was static — there are bright individuals and bright movement but taken as a whole India was static. In fact India was static before that. […]. Even before the British came, we had become static. In fact, the British came because we are static. A society which ceases to change ceases to go ahead, necessarily becomes weak and itis an extraordinary thing how that weakness comes out in all forms of creative activity.”(Nehru, 1957).59

New, like change, like progress, like modernity – simply like good. A western ideology constructed through the establishment of its opposite. The Other. Their histories stolen, their traditions suppressed, their identities denied. To be, is to be white. Internalised inferiority therefore speaks the language of desire. “Then I will quite simply try to make myself white: that is, I will compel the white man to acknowledge that I am a human.”60 – Fanon writes this in his seminal book Black skin white masks and concludes later: “I am overdetermined from without. I am the slave not of the „idea” that others have of me but of my own appearance.”61 Whiteness, explains the Pakistani writer Ziauddin Sardar in his introduction to Fanon’s book, becomes synonymous with purity, Justice, Truth, virginity. “It defines what it means to be civilized, modern and human.”62 Let’s connect the words differently. It is the purity of the form. So pure, that it is nothing but the absolute. An embodiment of a higher Truth. To be found inside the form, but outside. Its virginity, proclaimed neutrality. Neutrality, like fairness, like Justice. Justice, the achievement of civilisation. The victory of an enlightened humanity. Enlightened humanity, or Modernity. Or Le Corbusier. His most celebrated building in Chandigarh, the Palace of Justice (fig.3). Le Corbusier is modernity, modernity is Chandigarh, Chandigarh is the form, the form is pure, it is truth, it is just. Just the form. Or everything the other way around. The pure form, its value, its price.

Image Credits: https://www.eruditionmag.com/home/what-if-le-corbusier-is-not-also-jeanneret-a-creative-investigation

The Other needs to suppress himself to be recognized by the white man as a human. Le Corbusier needed to suppress his sympathy for Hitler, the Fascists and his collaboration with the Vichy Government to be recognized until today as the prophetic light of a new humanity.

“We must rediscover man. We must rediscover the straight line wedding the axis of fundamental laws: biology,nature, cosmos.” (Le Corbusier, The final Testament).63

Le Corbusier devised – what he called – a masterplan for Chandigarh. For the City and its Capitol, the prestigious government district. Due to several disagreements, Le Corbusier withdrew from the realisation of the City itself, executed by his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, and instead concentrated fully on the realisation of the Capitol, with its Palace of Justice, an Assembly Hall, a Secretariat and a never built Museum of Knowledge.64 “My palaces 1500 meters away fill the horizon better than at 650 meters. … The scale is more noble and grand from a distance.”65 From a distance, they should be admired. These palaces of modernity. Their rational-scientific objective style – their universality. The enlightened institutions they harbor. The values they express. Their material, their architect. A self-identical unity. These symbols of a modernity, detached. Their appropriation denied. To appropriate it to oneself, to interpret it. Le Corbusier prohibited the realisation of any other buildings in a great radius around the Capitol Complex. Equally, the standardisation of the houses in the City was to be respected. A frame-control system regulated any private constructions in the whole city.66 Appropriation denied, but appropriation of land and its expression of a future, once again. Chandigarh, India’s monument of modernity. It’s symbol of a new beginning. Chandi, in the Hindu cosmogony is the “[…] energy, the enabling force of transformation and change.”67 There was, and still is a temple for this goddess. Never intended to be integrated in the City’s plan, it became its margin. Chandi also was the name of one of 24 rural villages and its 9000 inhabitants, which were forced to relocate.68 Chandi, substituted by Chandigarh, its proclaimed antithesis. To be new is to be unfettered by the past. This Nehruvian doctrine. This internalised colonial doctrine. Constructed oppositions. In hierarchy: old/new – traditional/modern – backward/progressive. It’s violent anchoring in cultures to raise boundaries. Its inscription on bodies to mark them as inferior. A binarisation and its equation with value. The new – this fetishized value in itself. And the internalisation of being valueless as the inferiorised Other. Homi Bhabha asserts: “First: to exist is to be called into being in relation to an Otherness.”69 It’s the cause of a desire, it’s the longing for an escape out of the assigned epidermalized inferiority.

Fanon detects this violently nourished inferiority complex especially in the educated Elite.70 To speak the colonizers language, to read his books, to share his taste and his philosophy. And to be the Other, still. “Modernization, thus, was a mimicry of the colonial project, of the aims and aspirations of colonization, imitated and re-legitimzed by the English-educated, Indian elite.”71 It’s the reproduction of a colonial value system, it is, as Vikramaditya Prakash, an architect grown up in Chandigarh puts it, the continuation of a constructed mutual exclusivity. Chandigarh is perceived to be modern, because it’s un-indian. It’s un-indian because it’s modern.72 However, Le Corbusier consciously decided to retain one rural village, which he delicately included into the view from the Capitol. Maybe in the way like a pseudo-ancient roman monopteron is integrated into the view in an English Garden. “For not only must the black man be black; he must be black in relation to the white man.”(Frantz Fanon)

Alienation and romanticisation of a lived tradition. No permeation but, as the western museal logic teaches, preservation. The Capitol, in its detachment from the City, becomes the ideal vision, the expression of a supposed universal liberty, in distance. The rural village, in turn, in its detachment from the City and the Capitol, becomes the ideal vision, the romanticisation of the noble savage, in distance.73 Sight, this overburdened sense of the West. The view on the Capitol, is a view on a symbol for modernity — an intangible vision. It is not the self-spun vision, which gets tangible in the process, and visible, when it is carried out in a collective act on the bodies of the people – as their symbol of a modernity in independence – in progress. The spinning wheel – this was the counter-vision to this violent ideological construct, which equates modernity with the West, and grounds it in exclusivity by breeding an opposed Other. The entanglement of their histories encloses itself in the object, which by reducing it on its outer appearance gets purified, to deny its inner impurity. To understand the latter is to overcome ones own internalised inferiority. It’s to understand that one was never just outside an supposedly exclusive Western modernity.

Charkha. The reclamation of the materials, thus of the land — the execution of a self-determined work, thus the reclamation of ones body — is to understand the history of one’s own dependence through the spinning of a vision of independence. It’s to understand that when land and body, or better the extracted value of land and body, not gets coercively taken away, to be abstractly re-imported as genuinely western value, supposed to be an expression of an exclusive western modernity — modernity can instead be developing on site.

In 2016, the Capitol Complex was marked by UNESCO as a transnational World Cultural Heritage. Transnational, not because of the inseperatability of shared histories, but simply because Le Corbusier’s buildings, to which this award is dedicated, are to be found all over the world. Or rather an expression of modernity, which is understood to be singular and is then in turn equated with a single white man, is understood to be transnational. The reason to pick 17 buildings of Le Corbusier was their pathbreaking character, their exemplary expression of modernity.74

Provoked was this method of preservation by the decay of the buildings and their plundering. As India’s proclaimed monument of modernity it got appropriated for a little amount, for its little value. To get its value then defined – when it gets extracted – from the outside – in the outside – when its value is realised. This value of the Exterior Light by Le Corbusier.

2010

London & Zurich A day inSeptember

All these little discrepancies in the end: That it gets forcefully scattered – this monument of modernity – belonging to those who nevertheless do not have the privilege to receive its value. Neither its economic value nor the liberal values it expresses. Thus, that there is no value, no respect given to its unbrokenness as a monument in Chandigarh, but that it gets its value defined pars pro toto somewhere else. To substitute the whole through a little part and to make it then incredibly valuable in turn as representation of this whole. To not value the monument but to make it valuable, thus sellable as Monument of Modernity.

And then its preservation. Making it a World Cultural Heritage, to stop it’s problematic sellout. To replenish it with value again. With cultural value, thus economic value. To increase the price globally, for instance, for everything that is to do with Le Corbusier. To claim it a Cultural Heritage is to hold together that, which got and got to be dispersed. Its scattering and its preserving — both due to its being a monument of modernity.

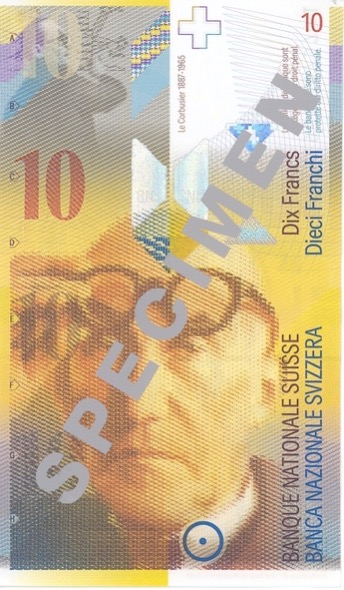

In the end it still seems to be a genuinely western matter to decide what is an object – what can be exchanged as a commodity – with what value it can be ascribed and what value can be extracted from it. This couldn’t better be symbolized than by finding Chandigarh’s Capitol on a currency, which is not the Indian. One spots the ground plan of the Capitol on the 8th Swiss banknote series (10 franc note) (fig.4), claiming it the cultural heritage of Switzerland, just because Le Corbusier, though having a french citizenship, was born there. Chandigarh, its extracted value thus again in circulation as value.75

The genesis of the abstract, of Capital, enforced the entanglement of histories through violence, which then, for the sake of cultivating ones own superiority, got denied. The symbol of India with which it claims its independence from these violent power relations, now on the currency of a country which occupies the first place on the Global Innovation Index (2019), a country in which every tenth adult has an asset, higher than one million dollar.76

Value is a currency and currency is abstracted value. To make it one dimensional is to let the abstract feed itself.

Image Credits: https://www.snb.ch/en/the-snb/mandates-goals/cash/series-8/design/10-franc-note

Biografie

IMKE FELICITAS GERHARDT studierte Politik und Kunstgeschichte an der Freien Universität Berlin, wo sie kürzlich ihren Master in Kunstgeschichte abgeschlossen hat. Ihr primäres Interesse gilt Moderner- und Zeitgenössischer Kunst, Media & Performance. Im Anschluss hat die Autorin Tanz am Trinity Laban Conservatoire in London studiert. Der Fokus ihrer theoretischen Arbeiten liegt stets auf der Analyse von Machtverhältnissen. Dabei ist es für sie als Kunsthistorikerin und Tänzerin vor allem interessant, wie sich Macht in visuellen Regimen ausbildet, wie Macht in Körper eindringt und Objekte formt. Ihrem Interesse für Poesie geschuldet, versucht sich Imke Felicitas Gerhardt an einem experimentelleren akademischen Schreiben, da sie der Auffassung ist, dass Kritik nur eine Wirkung erzielen kann, wenn sie die Struktur der Sprache und Kommunikation herausfordert, in der sich Ideologie versteckt.