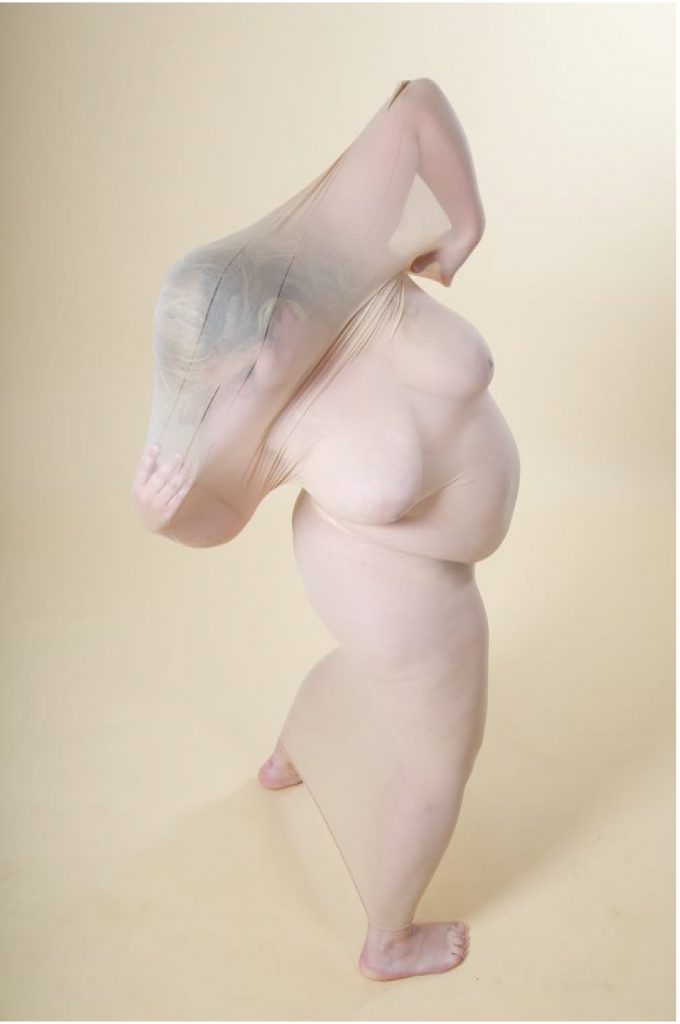

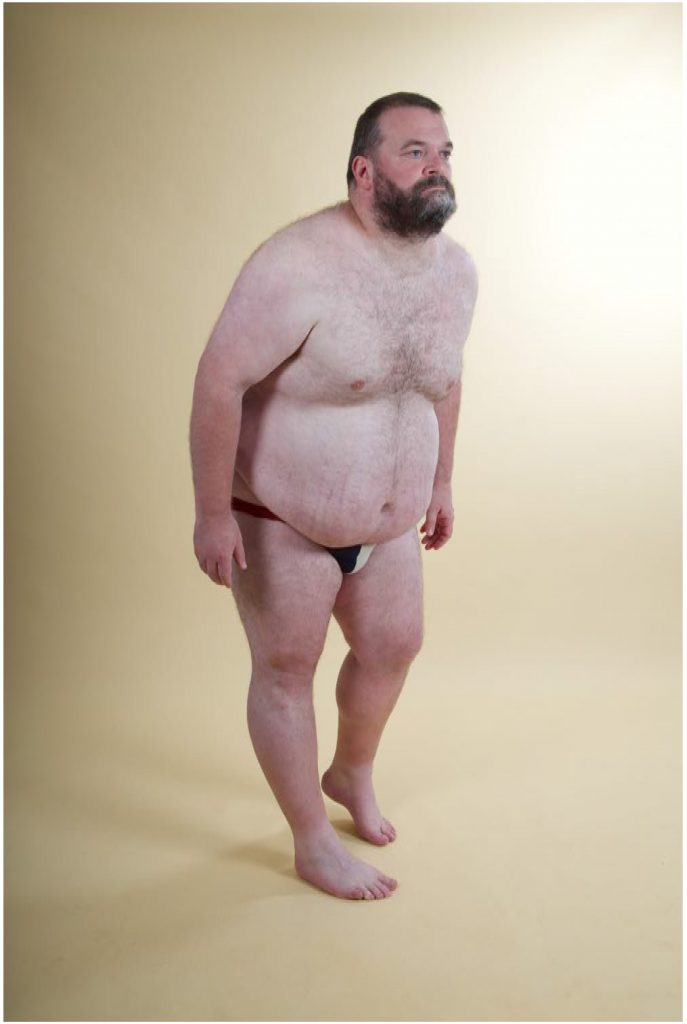

In ihrer Arbeit EXTRA BOLD zeigt Carmen Westermeier, in der für sie typischen forschend-kritischen Weise, Ergebnisse einer langjährigen Auseinandersetzung mit der Hyper(un)sichtbarkeit dicker_fetter Körper. Für frame[less] führt sie mit Fotografie und Text durch die Sphären der Sicht- und Unsichtbarkeit normierter Vorstellungen von Körper und Gewicht. Dabei zeichnet sich eines deutlich ab: das Bild des dicken_fetten Körpers als widerständigem Akteur.

We are all visible and invisible at times […], but one’s situation becomes “hyper” when (in)visibility becomes socially oppressive.1

My parents were pleased that I had gotten my body under control. I went back to school, and my classmates admired my new body, offered me compliments, wanted to hang out with me. That was the first time I realized that weight loss, thinness really, was social currency.2

Doch womöglich sind die entscheidenden Gründe für die Stigmatisierung dicker Menschen weder allein in der Frage nach den angenommenen Ursachen des hohen Körpergewichts noch nach den individuellen Anstrengungen zur Reduktion des Körpergewichts zu suchen, sondern in einer soziokulturell verankerten ästhetisch motivierten Ablehnung dicker Menschen. Dies jedenfalls legt eine Studie von Vartanian und Novak (2011) nahe, die den weit verbreiteten „Ekel“, (disgust) vor Körperfett als entscheidenden Grund für Gewichtsdiskriminierung ansieht und wesentlich relevanter einschätzt als die Frage nach den möglichen Ursachen des erhöhten Körpergewichts.3

These stereotypes assume that being fat is a choice— that a corpulent body is evidence of overeating and thus a disordered, undisciplined self. Conversely, a lean figure represents selfmastery and control. Such virtues are tied to notions of good health, beauty, and broad cultural values like efficiency, speed, mobility—all of which reflect and support the prevailing economic system of consumer capitalism.4

Fighting the fat self […] I argue that this paradox is best explained by the phenomenon of hyper(in)visibility. The constant attention that is placed on “obesity” by the media, politicians, and the medical community perpetuates the idea that fat is—or should be—a temporary state, because “responsible fat people” should always be trying to lose weight. The majority of women in this study identified with these

larger cultural values and have internalized fatphobia— they remain hidden or in the closet. As a result, their enactment of stereotypical behaviors is a reflection of internalized oppression.5

[...]common sexual activity known as the ‘Rodeo’. This practice involved a group of about ten cadets, who would gather in a hotel room. The boys would make an agreement that one of them would go out to a local pub or club, and find the most obese woman he could, pretend he was sexually interested in her, make her feel desired, and then lure her back to the hotel room. The other nine boys would wait in the hotel room for the couple, hiding behind couches, in the bathroom, in wardrobes. Once the young male cadet and the “fat” girl arrived, the boy would seduce the girl, and begin to undress her, encouraging her to be lieve that he was about to have sex with her. He would then ask her to kneel on the bed on all fours, and he would pro duce a scarf to blindfold her. The “fat” girl would be lulled into thinking this was just a kinky start to sex with the young cadet. Instead, the young boy would call out a signal to the other boys and they would run out from their hiding places. One by one, they would jump on the “fat” girl’s back, kicking at the soft flesh of her hips and belly, riding her like she was some sort of animal. They would ignore her tears and her screams, and once they had all had their turn, and the “fat” girl was completely humiliated, they would kick her out of the room. 6

According to blogger Virgie Tovar, it’s both a product of the larger cultural hangups around body image and masculinity itself. “Fatphobia in so many ways is about hating and policing women and our bodies, but what I’ve realized recently is that in some ways, the fatphobia that fat men experience is also a result of misogyny,” she writes. To be overweight is, thus, to be considered simultaneously weak and feminine, so much so that the Grindr commandment against “fats and femmes” is almost always a package deal. [...] These ideas are particularly harmful for gay men, many of whom might have grown up internal izing negative messages about queer people from a young age. Homophobia itself is rooted in misogyny: It’s bad to be gay, because having sex with men is something that a woman does.

As Simon Moritz explains in the Huffington Post, slurs like “fairy” and “sissy”have a dual meaning rooted in antigay and antiwoman bias: “They prize masculinity by

demonizing femininity.” […] The gay community’s toxic masculinity problem isn’t just an issue for those who are told they "need to lose a few pounds", but everyone who is told that they don’t fit an unrealistic standard of physical perfection—including those who are too skinny, too short, or not white. 7

However, the mind/body split contributes to self objectification and hyper(in)visibility when fat women see their bodies as abject or as objects of revulsion— something separate from the real them.8

Assumption: If you’re fat, there’s a thin person inside you. New Version: And if you’re thin, perhaps one day you’ll realize your true fat potential. […] Assumption: Fat people eat all the time. New version: Thin people eat all the time, too. (It’s a great survival skill.) In fact, studies show that fat people eat the same stuff that thin people do, from burgers to broccoli. […] In our dietcrazy culture, when a fat person eats a bit of food, everyone notices. […] Assumption: […] Fat people are smelly, stupid, lazy, gluttonous, sexless freaks. New version: These are the same slurs that have been applied to every stigmatized group, from people of color to the disabled. In the psychology of oppression, if you can belittle someone and deny their humanity, then it’s okay to be hateful and prejudicial to them. 9

All Credits: Carmen Westermeier, EXTRA BOLD, 2020 ©Carmen Westermeier

Biografie

Carmen Westermeier ist Medien- und Performance-Künstlerin und Aktivistin in Stuttgart. Sie widmet sich einer feministischen Epistemologie und verfolgt eine körper-politische, künstlerische Praxis. Als freie Referentin kooperiert sie mit verschiedenen Initiativen deutschlandweit oder unterrichtete an der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität zum Thema Gender und Kunst. An der ABK Stuttgart forscht sie als wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin zu diskriminierungskritischen Positionen in der Kunstpädagogik.

Fußnoten

- Gailey, Jeannine A. (2014): The Hyper(in)visible Fat Woman. Weight and Gender Discourse in Contemporary Society, New York, S.8

- Gay, Roxane (2017): Hunger. A Memoir of (My) Body, New York, S.51.

- Rose, Lotte/Schorb, Friedrich (Hrsg.): Fat Studies in Deutschland. Hohes Körpergewicht zwischen Diskriminierung und Anerkennung, Weinheim, Deutschland 2017, S.320

- Lelwica, Michelle Mary: Shameful Bodies. Religion and the culture of physical improvement, London 2017, S.103

- Gailey, Jeannine A. (2014): The Hyper(in)visible Fat Woman: Weight and Gender Discourse in Contemporary Society, New York 2014, S.37

- Murray, Samanth: The ‘Fat’ Female Body, London 2008, S.122

- Lang, Nico (2017): Fat Shaming, Toxic Masculinity, and the Gay Male Beauty Myth. https:// www.thedailybeast.com/fatshamingtoxicmasculinityandthegaymale beautymyth [zuletzt aufgerufen 09.11.2021]

- Gailey, Jeannine A.: The Hyper(in)visible Fat Woman: Weight and Gender Discourse in Contemporary Society, New York 2014, S.58

- Wann, Marilyn: Fat! So? Because you don’t have to apologize for your size, Berkely 1998, S. 84f.